Portraiture

by Brooke DiDonato

American Sonnet for the Familiarity of Whiteness

What makes a sonnet American?

The nature of its self is to contradict

Contra indicate contra band contra ctualisms

Con straint is what it is to be abundant:

how slithered voltas abundant at you full

speed towards you like an eagle tucked into its

self in a bombardment of, like, capitalism.

I am unable to turn away, to become inescapable

the way I was promised: a rich lawn, good credit,

police as ally to my destruction, my whiteness.

My instinct: to seek kinship. Another: avoidance.

It is easier to embrace this: presumption pre:

Gone. I have a lot in common with other lowercase-

w white people: we get most everything we want.

Sophia Chester by Michaela Oteri

In disability studies, the emphasis on accessibility practices reveals horror stories of physical (and psychic) barriers to physical meeting spaces; digital spaces offer community without the constant challenges of no curb cuts, out-of-service elevators, chemical fragrances, and other common access barriers (Carr, Price, Clare). Moves into digital spaces subvert these access requirements by allowing for identity-based formulations of disability community instead of embodied identity-based affiliations found IRL. But, does this disembodiment equate to a form of posthuman identity? Citing Tiffany Lethabo King, I consider the interstices of identity and humanity.

In many ways, discourse surrounding the posthuman echoes the desire to distance the posthuman from the othered nonhuman. Historically, humanities study has used Kantian rationality as a basis for human identification; this narrative obscures the ways in which humanness has been used as a tool of oppression by categorizing people as nonhuman to justify violence against them. If posthumanism desires to fragment the Kantian subject, the “neutral” subject humanities study has centered since the Enlightenment, what of the marginalized subject, the embodied subject subjected to violence and oppression in the forms of settler colonialism, ghettoization—both geographic and intellectual—and architectures of oppression?

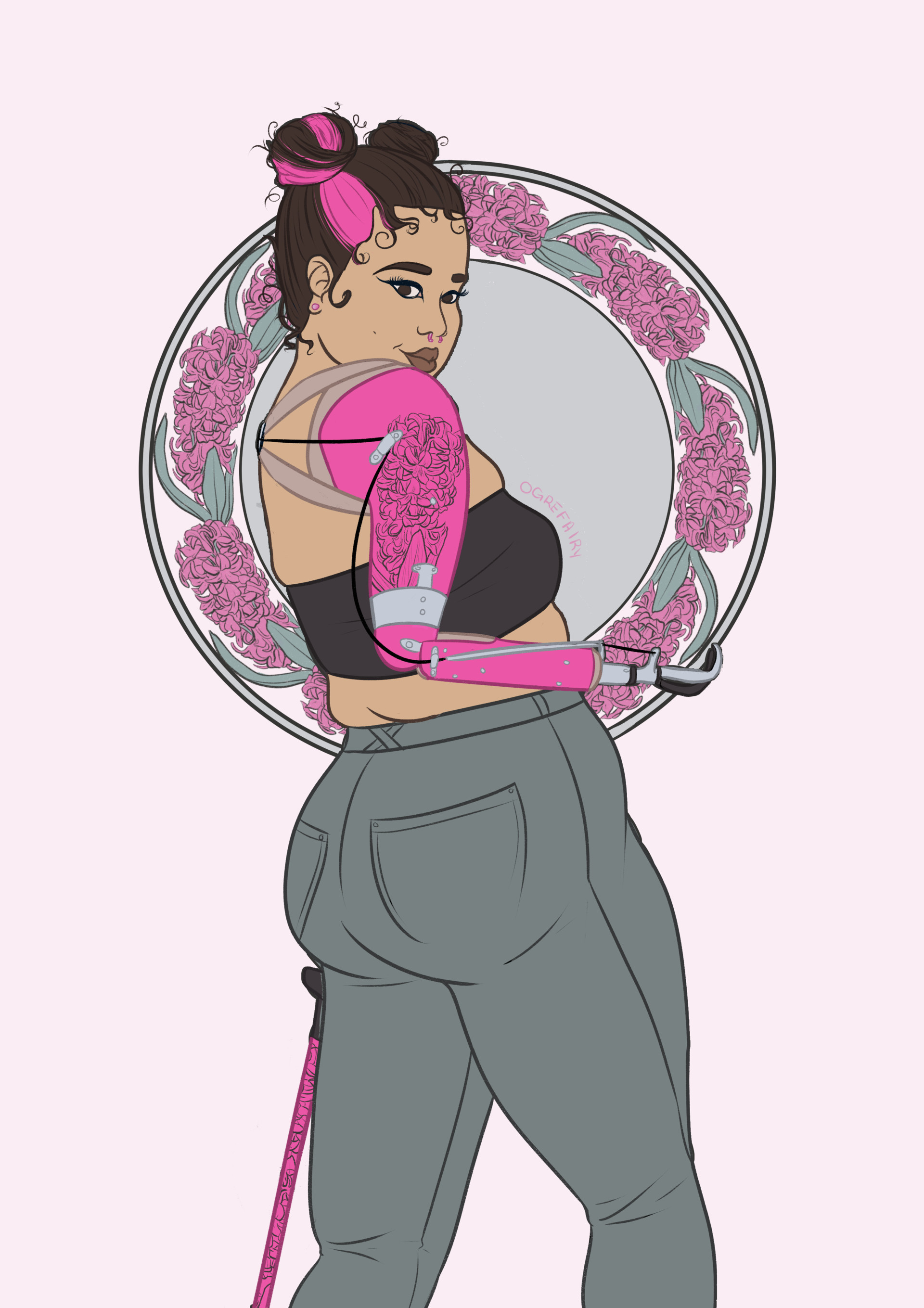

Annie Segarra by Michaela Oteri

By the term architecture here, I mean the systemic infrastructural conception of the human: the architecture of posthuman rhetoric, then, reifies and reinforces these ghettos to which the marginalized subject is confined. Through White, Wegenstein also identifies architecture as essentially technological, and in fact as a form of new media by how space is deployed and manipulated to differentiate subjectivity, perspective, and movement. However, these theories do not explicate how architecture is too the material exclusion built into public and private spaces that exclude sick and disabled subjects; a rejection of these architectures of oppression implement universal design, a concept of inclusive building and design that centers the needs of disabled bodies, or, in this case, any body implicitly or explicitly excluded from spaces where policy decisions, design values, and objectivist sciences of architecture occurs. Universal design, for me, includes rhetorics of access: jargon-free, natural language, but also a cultural ethos that values the importance of non-normative forms of communication—including minoritized dialects—that centralize an expansive definition of the human.

Posthuman rhetoric functions as colonial violence by further stripping the agency of radical subjectivities by defining them still as in the margins: “minority” language is deployed as code for unlike the human. The implicit affiliation of the author is with the reader: the us intends to include scholars in humanities study by treating marginalized rhetorics and identities as objects of curiosity, of study. This logic follows settler colonialist ideologies of occupying marginalized communities through the scrim of research, ensuring the objectivist stance fetishized by humanities study.

by Michaela Oteri

The further a subject is located from the idealized Kantian subject, the closer they (again, author identifies with the researcher) move towards the margins, which ensnare these objectified folks in a double-bind. The marginalizing architecture of scholarship includes the ineffectual nonprofit industrial complex, privatized medicine, the university: all well-oiled gatekeepers who welcome assimilated subjects while maintaining a closed-border policy to subjects unwilling—or unable—to pimp their own trauma for access to resources. Thus the snare of neoliberalism appears again: the uncooperative individual is to blame for their own struggle to survive.